Memoirs

Part 3

Martinus

Wasn't it while you were working at the dairy that you began to get interested in photography?

Yes, that's right! At that time amateur photography was something new and unknown. In larger towns there would be a real photographer with a studio to which one could go if, on the occasion of a wedding, a christening or some other family event one was to have one's portrait taken. They didn't use film but glass plates, and the sitter had to be completely still without blinking, since the exposure lasted some seconds.

One day I saw a newspaper advertisement with the headline: "Now everyone can take photographs!" The advertisement said that if one sent the sum of 11 crowns, 75 øre (There are 100 øre in a crown) to "The Amateur Photographer", Vimmelskaftet, Copenhagen, one would receive a package containing everything an amateur needed: camera, plates, darkroom lamps, deep trays for the developing fluid and fixing bath together with printed instructions.

That was just the thing for me; so I ordered and received this package. I studied the instructions, but they were very brief and, since I had no experience of that kind of thing at all, it took a long time before I succeeded in taking pictures. The instructions said that one should use a darkroom when one was to change the plates and when one was to develop them. But I didn't have a darkroom, and, since it was midsummer, it was very light.

But then I remembered that up in the loft there were a couple of large empty barrels. One of these maybe could be used as a darkroom. I placed a little stool in one of the barrels and crawled down into it with the darkroom lamp and the other paraphernalia. I had to sit with them on my knees. I had placed a sack over the barrel and now it was completely dark apart from a rather weak light from the darkroom lamp, which consisted of a candle in a glass with some red material around it.

As I began unpacking the glass plates, the lamp caught fire. I rushed to put the fire out, not thinking that that little bit of light could have ruined the plates.

Having placed the first plate in the camera, I was now ready to go out and take photographs. I didn't know how long an exposure I should use, so I held the button down for over a minute! That was of course far too long, and later, when I sat developing in the barrel, it appeared that the plate was overexposed and completely black. I tried with a new plate and exposed it for a shorter time, but the result was the same.

Then I remembered that there was a real photographer in Hjørring; so I took my bicycle and rode over to him. I told him of my troubles and asked if he could show me how a correctly exposed plate should look. He showed me a plate on which a room had been recorded and I was astonished to see how many clear details there were. He explained to me that all my plates had almost certainly been made useless when the lamp caught fire. He gave me various pieces of good advice and finally referred me to a new photography shop a little further down the street. Here I bought more detailed instructions and some new plates.

I didn't take any more photographs in Lønstrup because I now moved to Funen. I had a job at a dairy in Hesselager between Nyborg and Svendborg. I was there for three years, from 1st November 1908 to 1st November 1911.

It was the oldest dairy in the neighbourhood; it was very run down and had dreadful machinery; the sanitation would absolutely not be accepted today. But the year after, it was rebuilt and modern machinery was installed.

In my free time I cultivated my new hobby. I bought a larger camera; but I still made a beginner's mistakes.

On some of the large estates that delivered milk to the dairy there were many foreign workers, mostly Poles. I cycled out to these estates and took group pictures of the workers, promising to come back a couple of days later and show them the result. They all wanted to buy pictures.

I developed the plates myself, and when they had been rinsed they had to be dried. So that they would dry quickly I put them by the steam boiler. But it was far too hot there and the gelatine melted and ran, so that the sitters became long in the face. So the next day I had to cycle out to the Poles and take them again.

One morning I was terribly scalded in an accident at the dairy. Beside one of the machines there was a container of boiling water under the floor with a cover over it. While I had been outside for a moment another dairyman had removed the cover. I couldn't see this because of the great amount of steam there often was. I took one step into the boiling water. Taking hold of a pipe I pulled myself up, but my leg hurt terribly. I hopped around, groaning. When I finally got the sock off the skin came with it. My employer's wife came and helped me. The proper thing to do would have been to call a doctor, but they preferred to save the expense.

Instead a farmhand was sent to the chemist for some "Egg oil" (At the turn of the century this mixture of equal parts of lime-water and linseed oil was used as a burns lotion). Then my fellow-works sat round me until midday, taking turns at putting compresses on.

My foot cooled down a little so that the pain more or less away went, and then I went to bed, where I had to stay for a whole month. My only way of making the time pass more quickly while I was bedridden was reading some old crime novels. There was still no question of calling a doctor, but I had my foot bathed every day with home-made boric acid solution. It didn't help very much, however. When I finally got up I couldn't stand on that foot, so I was given work in the office.

At length I was able to resume my work at the dairy, but I still have scars where the skin came off.

But another time I tore a muscle. It began when I was to lift a heavy butter cask up onto a waggon, and then I got a stabbing pain in my back. After three weeks had passed I still had this pain in my back.

Then one day I, together with another worker, had to lift a very heavy cheese barrel up into a loft. Before we got it up I felt a very intense pain in my back, and I could hardly breathe.

I had to go to bed immediately. My employer came and comforted me by saying that it was probably just lumbago and that it would most likely get better by itself. I should just stay in bed for a few days. But I again felt terrible stabbing pains through the body.

The next day I realised that I had to go to a doctor. So I got up and walked to the doctor, who lived nearby. First he wanted to know if I had enough money to pay him, and then he asked if my parents had had tuberculosis.

When he found out that I had ruptured a muscle, the treatment he prescribed consisted of me having my back rubbed with iodine and I had to have a large towel wrapped tightly round my body. I didn't need to lie in bed.

My employer was rude to me - he didn't think that it was anything to go to the doctor for. But I thought that he could be quite indifferent since I would pay the doctor myself.

A week later I was fit again.

It has always been easy for me to get up in the morning; I can easily manage with five hours sleep. This was an advantage since the work at the dairy began very early. I was therefore assigned the task of waking all the others in the morning. One of those I woke was a dairymaid called Marie. Many years later, when I had long since moved to Copenhagen and begun my work as a writer and lecturer, I met Marie at one of my lectures in Odense. Now she had become a little plumper, and she was married. I thought I knew her face but I couldn't remember where I had met her. But then she came and greeted me, saying, "It's not the first time you have woken us up, Martinus!" And now I could remember her.

Wasn't it while you were at Hesselager Dairy that you began to be interested in conjuring?

Yes, it was at Hesselager. I had acquired various bits of conjuring apparatuses, some of which I had made myself. And sometimes I appeared before a reasonably large audience.

Can you remember any of your tricks?

I had one that I called "The Magic Ball". I used a red ball, about the size of a croquet ball. First I held the ball in my hand and pretended to give it some "magic" strokes, then I laid it on a table, where it began to move by itself. First a little one way, then the other way, and then a third way.

I had found the secret of the ball in the "Family Journal"; it went like this. Using a clever method one had to bore some very narrow channels in the ball. One then filled these channels with quicksilver. Finally the channels were closed and the ball painted. When one then lay the ball on a table with the right side up the quicksilver made the ball roll around for a whole minute.

I had a lot of other tricks on my programme, some with playing cards too. My most sensational trick was probably driving a car blindfolded. I had an acquaintance who placed his car at my disposal for this trick. (I myself had neither car nor driving licence.) I performed the trick in the market square, where a row of various obstacles was set up. The most sceptical member of the audience had to sit on the back seat just behind me, and be a supervisor. I sat behind the wheel and the car was started. In those days this was done by means of a crank in the front. I was blindfolded, and now we drove very nicely forwards through all the obstacles without bumping into any of them. I told my audience it was thought-reading that enabled me to do this. The man who sat behind me was to place his hands on my head, one hand on each side, and I was to read his thoughts.

It is really an art that anyone can practise. It is not thought-reading but muscle-reading. One just has to be aware of the supervisor's reactions. He of course didn't want me to drive into anything and he unwittingly made slight movements with his hands.

But the audience was impressed. "That dairyman knows more than his Lord's Prayer," they said.

One farmer had two sons, who liked me very much. Because I could conjure and be amusing I was often invited to dine with this family. It was otherwise unusual for servants and employees to spend time with the master and mistress and their family.

One farmhand was so jealous of me that he became angry with me. But I was always nice and friendly towards him, and it didn't take long before I had got the better of his antipathy, and then he became very happy and behaved decently to me.

When I had been in Hesselager for three years I wanted to go back to Jutland, and in November 1911 I got a job at the Møballe Dairy.

Møballe ("Maiden's buttock") is a strange name, which I almost didn't dare say at first. It was a large modern cooperative dairy near Horsens. Here I worked mostly on butter production. It was lovely clean work, so we wore white overalls. I was here for eighteen months.

I had a lot of free time and had many friends from the neighbouring farms. They were peaceful times: during the long summer evenings we lay in the roadside ditch amusing ourselves and enjoying each other's company.

I left there in May 1913, when I was called up as a marine. I was to travel to Copenhagen for the first time, but I spent a week's holiday at home with my foster parents first.

And then I came to Copenhagen, arriving the day before I was to report to the naval dockyard barracks. Copenhagen was the greatest adventure I had experienced up till then. There was so much to see: all the people, the elegant, beautiful shops, the lit-up streets, the Tivoli gardens and much more. For my first night in Copenhagen I had to stay in a hotel.

Next day I had to report to the barracks, where we were issued with our clothing; we had to sew buttons on for ourselves.

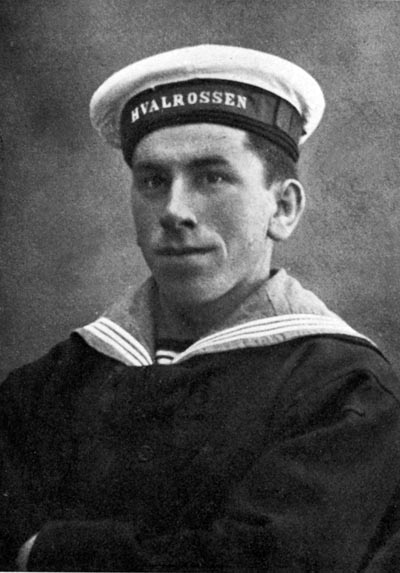

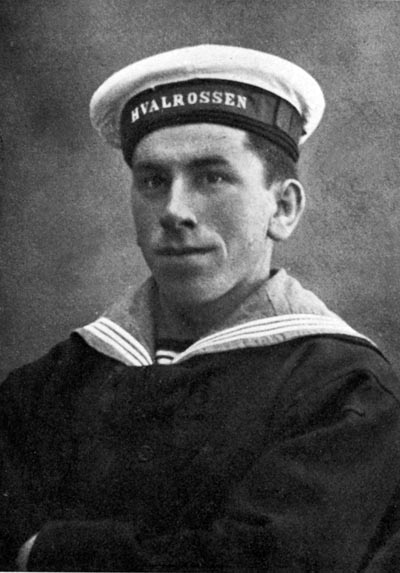

First I took part in some trial runs with a torpedo boat. The Navy had just had delivered some brand new torpedo boats from France, and the boat on which I served was called "The Walrus (Hvalrosen)". Some French engineers were on board during the first runs. The boat had a very high superstructure that turned out to be impractical, because when it met with heavy seas it would lurch so much that water got into the funnel. The boats had therefore to be rebuilt.

We lived in the naval barracks, and every day I was out on trial runs. I liked life at sea very much. It was summer, and the weather was lovely.

The boat could do 32 knots, but then it used 25 tons of coal per hour, and I was to help shovel it in. Because I was a dairyman and was familiar with steam boilers, I was signed up as a coal heaver. It was rather dirty and unpleasant work; after a spell of such work it was almost impossible to wash oneself really clean.

But then one day the chief stoker said to me, "You are obviously not used to such work but I will soon find a better job for you!"

When the trials were over, the boat was to go into service with the Navy. As the chief engineer needed an orderly I got the job.

Then I was very happy. The others called the chief engineer "Old Mouldy", but he was always very nice and friendly to me.

My job was very easy and quickly finished. I had only to polish his shoes and make his berth which was made up as a sofa during the day and as a bed at night. There were also a few small things I had to take care of.

The boat took part in some naval manoeuvres in the Kattegat. At night we sailed with our lights off and, under cover of darkness, we had to try to get so close to the big ships "Peder Skram" and "Herluf Trolle" that we could "torpedo" them. We succeeded several times.

As an orderly I didn't have to take part in the manoeuvres, but could go up onto the deck and enjoy the whole show.

When we lay in one port or another my commanding officer knew that I wanted to go ashore, so he gave me shore leave long before the others got it. I became very sunburnt that summer. I was already rather dark. One day an officer from another torpedo boat came on board. When he saw me he said, "What kind of an Indian is that you have there?"

There was always a cheerful and friendly atmosphere. Because I came from the country I was an easy victim for the others' "funny" stories. I had never heard anything like them before.

We were to learn to row, so we got into some large rowing boats. At first some of us would fall over backwards. One day the officer said, "Do you realise that on Friday we shoot all those who can't row properly?"

"No - I didn't know that," I answered.

When we had finished with the navy in the autumn, we lay in dock, where we were to work with the permanent staff. They were very kind and decent. I was often invited to coffee in their homes in Nyboder.

While I worked in the dockyard I lived and had my meals for a couple of months on "Peder Skram". But we worked as little as possible and the permanent staff did even less. They could sit on the toilet for hours on end reading the newspaper.

Towards the end of my naval service I worked on the royal yacht "Dannebrog". The ship was to be repaired, and my work consisted mainly of painting the windlass and other metal parts with red lead.

Now it was February 1914 and my naval service, which had lasted eight months, was over.

At that time no one dreamt that the First World War would break out in six months. They were peaceful times, and there were well-known politicians and others who said that people were now far too highly developed to go to war. There was, however, one person who said to us at our demobilisation, "You will see -you will soon be here again!"

I went back to my foster parents in Sindal and from there I tried to find a job again. I got one at Tirstrup Dairy on Mols. It was a little dairy; I stayed there only until September since the pay wasn't good enough. But while I was still in Tirstrup the war broke out. This was in August, and, even though our country was not involved in the war, I expected that I would be conscripted rather quickly. But it took some time because they first called up those who lived on Zealand.

In September I got a job in a large cooperative dairy in Skals near Viborg. But in November I was called up and had to go back to Copenhagen, and now I was a marine again.

Because of the many call ups the barracks were very overcrowded. But there were no officers; they were out on the ships. For this reason some ordinary national servicemen were put in command. But as they were not taken seriously there was much insubordination. The funniest thing was at night in the dormitory, where it was difficult to get a night's rest. And so, when one of the national servicemen who were in command came in and demanded quiet there was someone at the other end who crowed like a cock and another who barked like a dog. When he then came down to that end of the room it was completely quiet -but then the noises began somewhere else. I lay under the blanket laughing, but I didn't dare laugh out loud when he was close by.

After this had gone on for a few days one of the crew told me that he was being sent home the very next day. I asked how that was possible.

"Because I have bad teeth. One can be rejected for that."

"Then I want to be sent home too because I have bad teeth too."

I went to see the naval doctor and he referred me to the surgeon commander. He made all possible objections, but I continued to claim that I couldn't chew navy rations. He wanted to know what I usually ate in my civilian life.

"I eat milk foods, porridge and that sort of thing."

He probably realised that I was exaggerating since I could of course eat other things. But he couldn't get round the fact that I had bad teeth. And so I came before a rejection court, where I was freed from further military service and could go home.

Rumour spread among the marines at the barracks that one could be rejected because of bad teeth and some made an attempt, but now the doctor put a stop to it.

Before we leave your national service we would like to know how you saw your role as a marine.

I have always regarded the military as a necessary evil. But at that time conscientious objection did not exist; otherwise I would have chosen that. During most of my time as a marine I was not under command, and I have never borne arms. If I had come into a situation where I was supposed to use firearms I would have shot straight up into the air. In any case it would have been very difficult for them to teach me to aim with a rifle because I can't shut one eye at a time.

Then I got a new job as a dairyman at Herrested Dairy on Funen. It was a large modern co-operative diary and I was there until November 1915. I made a lot of friends there and, when they realised that I could conjure, I was encouraged to appear in the village hall which was chock-full with farm-owners and farmers who had never seen anything like it before.

I kept my job at this dairy for ten months.

Why did you change jobs so often?

There were various reasons. Partly because I wanted to get out and about; partly because I wasn't completely happy in all the places. At one dairy the owner wanted me to water down the milk, but I wouldn't. At another dairy the manager took every opportunity to go to the inn and get drunk, and then I had to manage both my own and his work and have responsibility for everything.

Another reason why I had to leave a job was of course that I had to go into the marines.

While I was at Herrested I sometimes cycled to Hesselager, where I had been employed in the dairy four years previously. Here they very much wanted to have me back and I accepted the offer; so from the middle of December 1915 I was once again employed at Hesselager Dairy. I had many old friends and acquaintances there and they were all very nice, even the farmhand who had once been jealous of me. We sometimes went on cycling trips together through the beautiful Funen countryside. We talked about all sorts of things, and one day he mentioned that he was afraid of ghosts. I decided to play a trick on him, and one dark evening I lay in wait behind a roadside tree, where I knew he would come past on his bicycle. When I saw him coming I put a white sheet over my head and stepped forward, waving my arms and shouting, "Ooh hooh!" He was instantaneously in a great hurry to tread on the pedals and get away.

Employees at Enigheden Dairy, 1922. Martinus is the third from the left in the front row.

Employees at Enigheden Dairy, 1922. Martinus is the third from the left in the front row.  Every evening I travelled by train to Vedbæk wearing my nightwatchman's uniform. I had night duty at Bakkehuset from 10 p.m. till 6 a.m.

Every evening I travelled by train to Vedbæk wearing my nightwatchman's uniform. I had night duty at Bakkehuset from 10 p.m. till 6 a.m. The following Sunday I was to visit his family, who lived in Slagelse. We were to make the trip by cycle, and I had been invited along. We cycled to Nyborg and took the ferry to Korsør. From there we cycled to Slagelse, where we had Sunday dinner with his family.

In the evening when we were cycling back by the same road I asked him if he hadn't met with a ghost the other evening. Now he realised what had happened, but he could not help finding it funny.

At this dairy I was concerned with the production of butter, and I now reaped the benefit of the experience in this field that I had had in some of my previous jobs. I succeeded in raising the quality of the butter so much that it came up to the same standard as the best in the country.

But now, having been a marine, I had a great longing to go back to Copenhagen. I applied for a job at Ishøj Dairy, which is situated close to Copenhagen. I got the job and began there in April 1917.

The owner was a lovely man; I was very happy there. Besides me there were two other dairymen, who were both married and had children. But in the long run there was not enough work for all of us, and the owner had to sack one of us. Since he didn't think that it was right to dismiss one of the married ones he talked to me about it. We agreed that I should try to find something else, but until then I could stay with him. I hadn't imagined that I would be a dairyman all my life, but I had to have something to live on.

We have now reached January 1918, and one day I went into Copenhagen. I had had the idea that I would try to get a job with a security firm (Vagtselskabet). I presented myself at their main office and asked the man behind the desk if they could use me.

The man looked at me a little, and then, showing me a large pile of applications, said, "You can see that it is rather hopeless!"

But in one way or another he must have trusted me because he suddenly said, " Can you come at once if we suddenly need someone?"

"Yes, certainly."

I went back to Ishøj and within the week there was a message saying that I should report the next day to the security firm. Here I was now taken on and was issued with my uniform. My first job as a nightwatchman was to be in Nordhavn (North Harbour).

There I walked and patrolled every night and watched the waves on the water. It was very quiet and peaceful. A watch inspector came round every night. After a couple of weeks he said, "We will soon find a better place for you, so you don't need to walk here any longer."

After only a few days I got a message that I was now to be the nightwatchman in a large villa with a park in Vedbæk.

A watch inspector accompanied me there on the first evening. We went by train. The villa was very large and lay in a 45,000-square-metre enclosed park, where roe deer roamed. The owner was Johan Levin, a stockbroker who had made a lot of money during the war. The villa, which was uninhabited in the winter, was called "Bakkehuset", and the address was Strandvejen 373.

The owner and his wife lived in the winter in a 24-bedroomed apartment near the Marble Church in Copenhagen, and only moved back to Bakkehuset in the spring. Some months passed therefore before I met the master and mistress.

I had my lodgings in the Nørrebro district of Copenhagen. They were in Frejasgade (Freja Street). Here I lodged in a little furnished room. But my landlady was a little difficult: she was over-careful with the furniture, and she covered the sofa and the armchair with newspaper. She was afraid I would make them greasy; I lived there for only a few months.

Then I got a better room at Jagtvej 52A. My new landlady was called Mrs. Henriksen.

Every evening I took the train to Vedbæk dressed in my watchman's uniform. I had to report for work at the villa at 10 p.m.

There were some control clocks in the park that I had to wind up at particular times. In this way one could see that I had done my nightly rounds at the right times. This was checked by an inspector every night.

Down in the park there were a couple of older houses. One of them was used by the gardener, who lived there all the year round. I was allowed to use the other house, and when I wasn't out on my nightly rounds in the park I sat in there and made myself comfortable.

How did you pass the time?

I sat and read books and magazines. Or I practised on a violin that I had just bought.

After some weeks the inspector said that now I could be free of the control clocks in the park

"We have to use them in town, but they are not necessary here. You take care of what you are supposed to, even if we don't inspect you!"

I was not allowed into the master and mistress's villa. But the gardener had access to the central-heating installation in the cellar of the villa. He had to see to it that there was a little warmth in the villa throughout the winter.

One evening at the end of April, when I arrived at the villa as usual about 10pm, I could see that the master and mistress had moved in.

When I did my first round in the park the master caught sight of me and called to me, "Hallo, are you the nightwatchman? How are you getting on? How are you?"

He asked me about various things and finally he handed me a little coin. I thought at first that it was a 10-øre piece but then I discovered that it was a gold twenty-crown coin. I later received many more gold twenty-crown coins. He was extremely wealthy - money just flowed in.

The master and mistress had a waiter, a chambermaid, a cook, a chauffeur, a gardener and a nightwatchman. The latter was me.

Despite the fact that there was a shortage of everything during and after the First World War and the government bad introduced rationing, one could not feel any shortage of anything in that house. There was no lack of fuel, petrol, coffee, sugar, clothing or other necessities of life.

When the weather was good enough, the master took a swim in the sea in the morning before he drove to his office in the city. He had his own private bathing jetty, and there was also a little beach hut. After his swim the waiter had to rub him down and act as his dresser.

The master and mistress entertained a great deal. When they didn't have guests themselves in the villa, they were invited out almost every evening. Among the guests I often saw Adam Poulsen, the actor, who was later the director of the Royal Theatre for a while. Prince Gustav was also sometimes their guest.

Sometimes the waiter tipped me off that the master and mistress would be coming home late from visiting friends or from a party given by some of their acquaintances.

"Make sure that you are down at/by the gate at 2.30 a.m. - you can be sure you'll get a tip." (Translator's note: Literally "skillling" farthing. - an obsolete Danish coin worth about a farthing)

The drive was furnished with a large solid wrought-iron gate, beside which was a pavilion with glass all the way around. Here I could sit for many hours during the night and enjoy the sight of the sea. And when the master and mistress then came driving in their limousine on their way home I was on the spot and opened the gate. And then I got the obligatory gold twenty-crown coin.

You were wide awake at the garden gate!

Yes, yes - you can be sure of that!

At midsummer great parties were held in the park with illuminations, bonfires and fireworks. And then the local population, which consisted of fisherman and country people, would stand on the other side of the hedge and watch the splendour of it. Sometimes someone would shout, "War profiteer".

Before the first summer was over and the master and mistress had left the villa to return to their 24-roomed apartment in the city they had got to know me so well that I was now given access to their villa during the night, so that I no longer needed to sit in the cold pavilion down in the park, but could stay by the central-heating installation in the villa's cellar.

Wasn't it there that you had experienced something supernatural?

Yes, that's right. It happened one night; I think it was a little after 2 a.m. As I sat reading, I suddenly felt that there was something there. I looked up from my book - and now I saw a figure standing over in the corner by a pile of coal. I recognised the figure; it was my cousin. She was the daughter of my foster parents. I wondered very much at this sight - she stood quite peacefully and still and looked at me. Then suddenly she was gone.

Some days later I received a message saying that she had died at precisely that time.

Another night I was likewise sitting in the cellar reading. Outside it was completely dark, but now I saw through the window that someone was coming. It was the watch inspector who usually turned up every night. He was wearing a uniform with shiny buttons; I could clearly see these buttons through the window.

I called out, "Come in!"

But then he disappeared into thin air. I couldn't understand where he had gone to, and when I met him the next evening I asked him why he had hadn't come in.

He couldn't believe that I had seen him, since he hadn't been there at all. He had been on his usual visit of inspection in Skodsborg; there he had been sitting chatting to someone and then had fallen asleep. In his dreams he had continued on his route, and I had experienced this "thought-picture" or "dream-vision".

On a later occasion I was sitting in the same way in the cellar. I had just been out on my midnight round of the park. Everything was quiet and peaceful. Suddenly there was an enormous crash, which rang throughout the entire house, as if it was about to collapse. I got up and touched my head. I felt that my hair was on end.

Can you describe the sound in more detail?

Yes - if you can imagine how it would sound if someone in the room immediately above my cellar-room who a couple of grand pianos fall onto the floor from a great height. I first heard this tremendous crash, and there there were some jingling sounds, as if a mass of piano strings were vibrating. I realised of course that no one was throwing grand pianos around, but I had to investigate immediately what was going on. I spent a couple of hours walking through the whole villa, but there was nothing unusual to be seen neither inside or out. Everything was quiet and normal again, and I realised that it must have been a psychic phenomenon.

The next day I told the gardener about it when he came to see to the central-heating installation, but I soon regretted it because he was so terrified that he no longer dared to be alone in the villa.

He told me that Vedbæk's old inn had been situated there many years previously and that a murder had once been committed there. After such an event, he said, ghosts could easily appear.

Was that the only time you experienced this remarkable phenomenon?

No. A long time afterwards it came again, but then I was out in the park and the sound was no nearly so loud. I was walking past the windows when I heard the same sounds, but now it was as if they came from far away.

What impression did that kind of experience make on you?

I had previously encountered that kind of thing and I can't say that they frightened me; my foster mother had so often talked about such things.

I really liked my job as a nightwatchman, but there were not many night-watchmen who had such a pleasant job as mine.

But after a few years had passed I noticed that the master and mistress's financial situation was no longer as good as it had been. The gold twenty-crown coins became five-crown notes, and there were many indications that they would soon have to sell the villa. If that happened my pleasant job as nightwatchman at this villa would come to an end and then the security firm would probably assign me to another job where I would have to go round with keys to shops and factories in the side-streets and backyards of Copenhagen.

I didn't want this; so I now tried to find another job. I applied to both the police and the tramway company. The police told me that I wasn't tall enough. But I got a positive answer from the tramways. In the meantime I had, however, come to realise that that driving tramcars for the rest of my life was not something for me. There were other occupations that I thought would be more suitable for me - artist, teacher, photographer or the like.

But now I applied for a job with the post office. I presented myself at the Main Post Office (Hovedpostkontor), and there, together with some other applicants, I was interviewed by the head postmaster.

He gave us quite a little admonitory speech. He couldn't understand that young people wanted to apply for jobs with the post office. Here they could spend twenty, thirty or forty years without getting anywhere. Out in the commercial world they had at least the possibility of becoming something.

But it ended all the same with me being taken on, and I started my career as a postman on 2nd January 1920.

I had to report for work in the morning at the Main Post Office, and then I was sent from there to Købmagergade's post office or to another post office where they needed me.

I was issued with a tricycle with four sacks attached, and then I was to go out and empty postboxes. There was snow and ice on the streets, and I "skated" over Frue Plads and through Nørregade and Strøget.

It was almost the worst moment imaginable to begin work as a postman, firstly because of the winter weather with ice and slush and secondly because around New Year there are always exceptionally many letters and postcards with New Year greetings and bills. But the worst thing was that during this period there was a telephone strike. Since people couldn't phone one another they had to use letters and postcards. Just as soon as I had been round on my tricycle and emptied my forty postboxes, I would start again on a new round. The post-boxes were so stuffed with letters that sometimes they stuck out of the opening.

The four sacks that I had space for on my tricycle couldn't contain so many letters, and I asked my superior what I should do.

"You should just stick your foot down into the sack and stamp the letters thoroughly together!"

But I didn't like the idea of the letters being damaged in this way; so I was content with pressing the letters together a little with my hand.

I was supposed to have one day off per week. But if a post office suddenly needed a relief postman they could send for me; in that way I was cheated of many days off.

For a while I delivered letters in Nørrebro. Here I had to go up to the fourth or fifth floor in at least forty places. There were no lifts and, because of the telephone strike, there were letters for most of the residents. Sometimes, when I had been up with a letter to the flat on the left on the fourth floor and had come down again, I would discovered that there was also a letter for the fourth-floor flat on the right, and then I had to go up again. But I learned to sort the letters more carefully before I started my route.

When the last letter had been delivered I had one and a half hours free and could cycle home and eat. Although I lived in the room I rented from Mrs. Henriksen in Jagtvej, I ate at a guesthouse in the same building.

After lunch I had to report to the post office again and go out on the same route with forty fourth or fifth floors.

For some weeks I was transferred to Adelgade and Borgergade, which at that time contained many houses that were ripe for redevelopment. In this quarter there lived a lot of foreign workers with strange names; most of them were Poles. Many of them lived in the attics. One had to go up a hencoop ladder and across the attics. But the people were very sweet and decent. There was, however, one place where I got a thorough scolding from a woman. I delivered a letter that turned out to be six months old. The letter had fallen behind some shelves at the post office, and had lain there for six months. When she discovered how old the letter was she began to rant and rave at me. But I made a quick exit and got on with my delivery route.

One day I received a letter from my foster mother in Sindal, telling me that my foster father was dead. One day in January he had come home tired from his work felling trees in the forest. He went to bed immediately and the day after, 24th January, he was dead.

Now my foster mother bad to sell the house and move out. The little girl, Frida, whom my foster parents had adopted many years before, was now twenty and had her own home, and she looked after our foster mother for the last five years of her life. None of her own many children helped her in her old age, but I sent money to her every month.

In the guest-house where I ate, I sometimes sat and chatted with a young man who was a clerk at the large Copenhagen dairy "Enigheden (Unity)". He knew that I had previously been a dairyman and that I wasn't always too keen on my present job as a postman.

One day he told me that he was giving up his job at Enigheden. In March he was to begin a new job with another firm, so there would be a vacancy in the Enigheden office. He thought that I would like his job.

He suggested that I went out to Enigheden as soon as possible and talked to the manager in order to apply for the vacancy. Some days later I went there and met the manager. I told him what the situation was, that I had no office training, that I was merely an ordinary dairyman, but that I thought I could manage the vacant job.

The manager was very friendly and said that he would like to take me on a trial basis. He didn't think that it mattered so much that I had no office training, since many of the clerks were not nearly as good at arithmetic and writing as the dairymen.

Before I began my new job in March I had to give notice to terminate my job at the post office. There were a couple of other young postmen who likewise wanted to hand in their notice, and now we had to come before the chief postmaster together.

When he heard that we wanted to leave the post office he said, "That's what I like to hear! Staying here year after year leads nowhere."

I began working in the office of Enigheden's Dairy in March 1920. There were about 100 drivers employed in the dairy. They each had a horse-drawn milk float.

Every day the drivers had to fill in order forms specifying the goods they should deliver the next morning. It was a question of full-cream milk, skimmed milk, buttermilk, certified milk for children, cream, whipping cream, butter, cheese and so on. I had to collect all these order forms and calculate how much of each product should be produced during the night. By 4 a.m., when the drivers arrived, all the goods had to be standing ready to be loaded onto the floats, and the drivers then drove out to the customers, who were spread over the whole town.

The clerk whose job I had taken over was to help me the first days. But I didn't get much help from him since he went down with influenza, and I had to manage by myself.

My monthly salary was 285 crowns while I was employed on a trial basis, and it was a good salary, the same as I had earned at the Post Office. And when after a short time I became permanently employed I received a rise of 65 crowns.

We were 15 clerks in all, and we sat in a large office, each with his own desk. The others were a little younger than me. The bookkeeper sat by the window, and the door to the manager's office always stood open. I thought that Enigheden was a lovely place to work.

We had a lot of telephone calls with orders from the city's many dairies, and I, together with another clerk, had to answer them.

The 100-odd drivers, when they were not out driving, were down in the stables. The first day a clerk had to show me round the stables and presented me to the drivers. I was somewhat frightened when I heard how the drivers addressed the clerk as "stupid pig" and other things that one certainly cannot repeat. They were also very hard with one another. I thought, "Oh - is it the likes of this I will have to work with here?" But since I was always friendly though firm with them they soon liked me very much and we worked well together.

A driver could sometimes get himself drunk and forget to fill in his order for the next day. When he arrived the next morning there would be nothing for him, and he could risk losing his job. But then I came to his aid by filling in the order-form for him as well as I could. And then the driver would come the next day and thank me: "That was nice of you!"

Some days after such an incident another driver purposely neglected to fill in his order form. He was not drunk but he apparently believed that I would help at any time. I realised, however, that it would go too far if I let myself be abused in this way; so I did not fill it in for him.

The foreman at Enigheden Dairy was called Lyngsie, and one clerk had warned me against him. If I were one day to answer the telephone when he called, I should at all costs do everything I could to comply with what he said, otherwise I might be sacked.

One day I answered the telephone when he rang and asked to speak to the manager.

"Yes, one moment," I said, and rushed to find him. As he was not in his office, I ran down to the stables where at long last I succeeded in finding him. But Lyngsie had become furious at being kept waiting so long, and he wanted to know what sort of an impossible fellow he had been talking to.

Martinus as a marine

Martinus as a marineThe manager warned me to be more careful another time: "You have no idea how furious he was."

"Yes, but I had to try to find you!"

"No, you should just say that I am not in my office, but that you will see to it that I will ring later."

I gradually got on good terms with all the clerks. I was, as I mentioned, the eldest, being about 30 years old.

But the relationships between the clerks were not good: there was a lot of hostility and quarrelling.

So I tried to make my influence felt. I talked to them, and finally they became very nice and we got quite a different pleasant atmosphere in the office.

As I mentioned, it was my responsibility to answer the telephone. One day a man rang and asked to speak to the manager. He was sitting at his desk when I told him there was a telephone call for him.

He asked me who it was, and I told him the caller's name.

"Tell him that I am not here today," he said.

"No, I can't say that", I answered; "it isn't true!"

The manager was a little taken aback, and then he said, "Yes, but tell him I've gone to lunch."

"But that isn't true either!"

The manager was not used to being crossed in this way, and all the clerks present were now anxious to see his reaction. But surprisingly enough he didn't get angry. After a moment's deliberation he said, "Good - then let me speak to him!"

At times I speculated a lot about what would become of me. I did not have the same desires or tendencies as my colleagues, who devoted their time to falling in love and thinking about marriage. I realised that I would never marry: the thought of being bound to another person horrified me. But I thought too that it was terrible that I should continue as now going to work every day and writing down 10,000 numbers, and then going home and eating, and perhaps going to the cinema now and then. And then the next day again off to work to write 10,000 numbers and so oh.

I wanted so very much to find a job where I could be of benefit to other people. I speculated about becoming a missionary, but as I was not particularly church-minded, I had to put that idea out of my head.

At the office there was a young man who had another job. He was, like me, a clerk during the day, and in the evening he was a musician. His name was Ove Hubert and he played every evening in the Apollo Theatre, which was situated near the Tivoli Gardens.

One day he showed me a book that he had borrowed from one of the other musicians at the theatre. This musician also had two jobs: he was a writer during the day. His name was Lars Nibelvang, and he was very interested in religious philosophy.

He had lent one of his many books to Ove Hubert. I don't remember what the book was called, but it was about reincarnation and meditation. Things like that were completely foreign to me. When I asked him what reincarnation was, I got the answer that it was something to do with us having lived before.

Although it was completely new to me that we have lived before, I thought immediately that it sounded right. He explained to me a lot of what he had read in the book on this subject, and I thought that it was very exciting.

I said therefore that I would very much like to read the book, and some days later I got the message that Nibelvang would like to lend it to me, but that I should come out to him myself on Amager (an island forming part of the city of Copenhagen) and pick it up because he would like to talk to me. So, a few days later I went out to him.

- Can you remember what his address was, and when it was?

He lived in Christian Svendsens Gade. And it was some days before the Easter holidays in 1921, 21st March, I think.

He received me in a very friendly way. He was in his early forties. I was very impressed when I saw the mass of books he had on his shelves. Almost all his books dealt with theosophy, anthroposophy and similar religious and philosophical subjects. He was very well read and very taken up with things of that nature.

When asked me about my work and my interests I had to tell him that I had no knowledge of these new spiritual directions, but I was religious, and I had, as long as I could remember, prayed to Providence every day.

I learned that the term "prayer" also formed a natural part of the new spiritual directions, and this reassured me. If he had said anything else I would have left quickly. I cannot remember what else we talked about, but as I was about to leave I was permitted to borrow the book I have mentioned.

As I took leave of him he said, "You will see, you will soon be my teacher!" I thought it was strange that he should say such a thing, because I could not imagine it.

A couple of days later I took out the book in order to read a little of it. I never managed to read more than a couple of chapters. There were instructions about how one could meditate on Providence, and I thought I would try it. I later realised that I had come into possession of this book solely in order that I should carry out this meditation.

I followed the book's instructions, switched off the light, rolled down the blind, put a blindfold over my eyes and sat myself comfortably in a wicker chair. Now it was completely dark.

Suddenly something wonderful happened. I was thrilled by a feeling that I was confronted by something indescribably elevated. A shining point appeared in the distance. It came closer, and took shape as a human figure. I recognised this figure. It was Thorvaldsen's (a Danish sculptor) Figure of Christ. I stared in wonder at this phenomenon.

Then it became dark. I could not move at all. It became light again, and now the figure appeared in a natural size, and it was completely alive. It was brilliant white with blue shadows. The substance was as if made of thousands of microscopic sparks of fire. The light was so intense and alive that it reminded me of the sparklers one uses at Christmas.

For some moments I found myself again in darkness. But the light came back, and now the figure was enormous. It went up through the ceiling and down through the floor. I could see only the area around the waist of this Christ-figure of blinding sunshine. I sat as if nailed firmly to the chair while the figure slowly moved forward towards me. And in the next moment it went straight into my flesh and blood.

I was gripped by a wonderful feeling of elevation.

The divine light that had thus possessed me gave me the ability to see the entire Earth. I saw how the Earth rotated, and new horizons with mountains and valleys, countries and cities, continents and oceans appeared continuously.

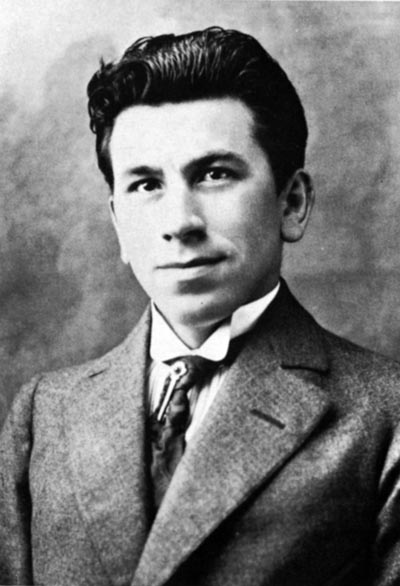

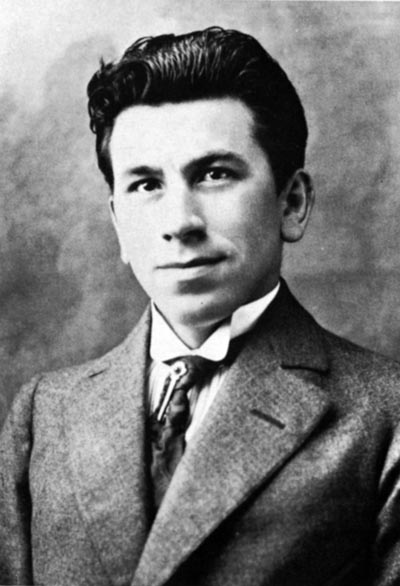

Martinus in the summer of 1921

Martinus in the summer of 1921When I could at last move, I removed the blindfold from my eyes. The divine experience was over. I was back in my modest material world. But the kingdom of God still shone and sparkled in my consciousness. I was completely overwhelmed and enthralled, but also very disorientated. I did not yet realise that it was an "initiation" I had undergone.

The next day was Maundy Thursday, 24th March, and I decided to try sitting in my "meditation chair" again. I was very anxious to see if something happened again.

I pulled down the blind, covered my eyes with a blindfold and sat myself in the chair.

I had only been sitting in the darkness for some few moments when I was again surrounded by the divine light. I found myself in a weightless state in the middle of a brilliant sky. A kind of shadow swept across the sky, and with this the sky became even clearer and more brilliant. This repeated itself, and each tune the sky became more and more radiant. At length I found myself in an overwhelming golden light, an ocean of fire. I no longer had a body, and I felt that this was the consciousness of God.

Then I had to tear the blindfold from my eyes because I felt that my brain was about to burst.

I found myself again in my primitive, sparsely furnished room. But I was completely spellbound, and I felt the need to confide in someone.

I went out into the kitchen to my landlady, Mrs. Henriksen. I told her about the wonderful experience, how it was as if I had found myself in the middle of an ocean of fire.

"Oh dear, you must not try such a thing, it can make one mentally ill" was her answer.

This was of course well meant of her, but I dared not tell her more; neither did I dare tell others about it.

But I now noticed that I had undergone a wonderful expansion of my consciousness. Every time I met a question or a problem the answer came immediately. It was exactly as if it was all "old knowledge". And I gradually realised that my knowledge had no limits.

I had to go about my work as usual, but when I came home in the evening I speculated intensely about what it could be that had happened to me. It was obvious that it must be connected with the book I had borrowed, and I therefore wanted to read more. But then I discovered that I couldn't. Every time I wanted to take hold of the book it was as if a hand laid itself on my forehead and held me back.

But then I discovered that I did not lack the information I could find in the book. I discovered too that it was impossible for me to read other books.

I had some time previously got myself a used piano on hire purchase, and I now had to sit myself down at it and play in order to get peace from the many thoughts that were flying around my head.

Some days later I went out to Amager in order to return the book to Nibelvang, and I told him what I had experienced.

He was completely enthralled. He was very well-informed in spiritual areas, and had knowledge of initiation, cosmic consciousness and the like, and he realised immediately what had happened to me.

Not for nothing had he spent years studying all the religions of the world. I have never before or since met anyone with such great insight into psychic matters. There were, however, many gaps in his spiritual knowledge, and he now confronted me with a mass of questions.

I was never in doubt about the correct answer to his many questions, but at first I very much lacked experience in expressing myself. The only things I had written up to then were some letters home to my foster parents, and now I had to answer a mass of complicated or profound questions. I answered them as well as I could, but it was seldom that he was satisfied with my answers immediately, for they did not always harmonize with what he knew from other sources. But it always ended with him exclaiming: "Yes, now I can see it. You are right! No one has ever been able to see that as clearly before."

Nibelvang and I became inseparable friends for a number of years.

The powerful experiences of light that had accompanied my "baptism of fire" had been such a strain on my brain that for a while I was plagued by headaches.

But I said a prayer that I might be freed from these pains, and now the pains were replaced by a pleasant warm feeling down my back.

As my work at the dairy did not begin until about lunchtime I visited Nibelvang almost every morning. He was originally called Lars Peter Larsen, but when he began his literary activities he changed his name to Lars Nibelvang. But among family and friends he was never called anything but "Lasse".

Thanks to Lasse my cosmic analyses became very strong and unshakable. He was the very incarnation of the spiritual questions of the whole of mankind. He knew almost better than I did which cosmic analyses or information people needed. He was stubborn and he was not satisfied until every problem had been turned over and over again and completely elucidated.

He was so full of enthusiasm and zeal that it rubbed off on me, and because of him my explanations became so firm that they could not be overturned.

We realised, of course, that this spiritual knowledge was designed for the whole of mankind, and that it should therefore come out in book form. As he had much more experience of writing than I had, it was a matter of course that he should write the book, and that I should merely explain and narrate.

But there was nevertheless something in me that said that I must be able to learn to write, and I therefore bought a typewriter.

And one day I wrote what is now the Postscript to "Livets Bog (The Book of Life)".

When Lasse read it he said, "I should not write anything! You must write the book yourself!"

And so I began to write.

But everything I wrote in the first years I had, however, to edit later. I was without experience, and I wrote such long sentences that they filled half-pages. In the beginning I thought it would be easier for the reader to understand the analyses if one did not interrupt the line of thought by using too many full stops.

Seven years actually passed before I was really ready to begin my main work, "Livets Bog".

There was a prolonged bodily cleansing and spiritual self-examination in store. I had never drunk alcohol or smoked tobacco, but I had eaten some meat. I had always been sorry that the animals had to be slaughtered, but I had always heard that meat was necessary because one could not exist without eating it. At that time there were not many vegetarians, but I myself had never been any great meat-eater, and it was not difficult for me to stop it completely. I felt, however, I ought not to cut it down too quickly, but after a few months I had completely stopped eating meat and fish.

At the guest-house where I ate, while the other boarders ate steaks and chops, I had at first to be satisfied with eating sauce and potatoes, and on open sandwiches, where before I had had liver pate" and salami, I now had Italian salad, vegetables and other vegetarian toppings.

There were also quite a number of other things, which had nothing to do with food, that I realised I had to avoid. I wrote about this later in my books and articles.

-----------------------------------

To be continued in Part Four

>> © Martinus Institut 1981, www.martinus.dk

You are welcome to make a link to the above article stating the copyright information and the source reference. You are also welcome to quote from it in accordance with the Copyright Act. The article may be reproduced only with the written permission of the Martinus Institute.