Memoirs

Part One

Martinus

Foreword (by the publisher)

When Martinus left this world on 8th March 1981 he was 90 years and 7 months old.

When he was about seventy he felt that he ought to write his memoirs. He gradually realised, however, that it would be difficult to find time to do so. He was at that time engaged in writing "The Eternal World Picture" - a work in four volumes known as the "symbol books". He expected to take a couple of years to write each volume.

He realised therefore that if his memoirs were to be written he would have to record them on tape. The tapes could later be edited by others to form a usable manuscript. Martinus approached me and asked if I would help him with this task. 1 was his neighbour and had known him for twenty-five years.

In the spring of 1963 we agreed that the matter should be tackled in the following way: Martinus was to present himself at my home on three evenings with weekly intervals. He wanted some of his old friends to be present. We invited therefore a married couple, Oluf and Kathe Palm, who had known Martinus for almost forty years, and Per Bruus-Jensen. Together we should form a "questioning team" that should "pump" Martinus for his memories.

The three evenings were informal. Evening tea was served and after a short chat Martinus declared himself ready to tell us all about his life. A microphone was placed on the table in front of him and the tape-recorder was started.

He then began to tell us about his mother, his birth, his childhood, his days as a schoolboy, as a herd-boy, as a candidate for confirmation, as an apprentice and as a dairyman. That was as far as we got on the first evening. We continued, however, on two more evenings.

The memoirs came to last almost five hours in all.

Martinus did not want his memoirs to be published during his lifetime; I therefore stored the tapes carefully and a couple of years after his death I had them transcribed. In the process of producing the manuscript I have tried to relate all Martinus' memories in the correct chronological order. I have also added some things that he remembered later.

October 1986, Frederiksberg

Sam Zinglersen (publisher)

Martinus, perhaps you would begin by telling us about your birth and who your mother was?

Yes - I was born on Monday 11th August 1890, near Sindal in the north of Jutland, shortly after midnight. My mother was unmarried; her name was Else Christine Mikkelsen. She herself was born in 1848 and was therefore forty-two years old when she gave birth to me.

She was housekeeper to Lars Larsen, the landed proprietor of the large farm "Christianshede", which was later renamed "Kristiansminde".

When at the beginning of 1890 she realised that she was pregnant she arranged, since she could not have me with her at the farm, that her half-brother and his wife should adopt me as soon as I was born.

This couple, Jens Christian and Kirstine Frederiksen owned a little smallholding called "Moskildvad", which lies seven to eight kilometres from Kristiansminde. In spite of the fact that they were poor and had eleven children already, they agreed to adopt me. Most of the eleven children were, however, old enough to have "flown the nest". They had gone into service leaving only two boys, aged three and five years, at home.

Early in August, when my mother realised that the delivery was imminent, she left Kristiansminde and went to Moskildvad. Since cars were a rarity at that time the short journey was made by horse and cart.

Late in the evening of Sunday 10th August it was realised that labour had begun. Midnight came and the clock on the wall struck twelve. As it finished striking something remarkable happened: the clock fell to the floor with a crash and was damaged beyond repair.

And so I was born!

Shortly after the birth my mother returned to Kristiansminde leaving me in the care of my foster parents.

... that was very remarkable ... it must have been a warning. It must have marked that one epoch was over and a new one had begun!

Can you tell us about the time immediately following your birth?

I was a very sickly baby; I lost so much weight that my foster parents did not reckon on my surviving. On 31st August they hurried to have me baptised. However, I survived the illness but was very puny. At school I was the second smallest of thirty children.

My foster father made his living as a roadmender on roadworks in the neighbourhood, and in the winter by felling trees in Slotved Forest with the forester. To the house belonged about five and a half acres of land, where his only cow and some sheep could graze. He also had permission to let the animals graze along the road and on the hillsides. He kept pigs and hens too.

Can you tell us anything about who your real father was?

Actually I have never really been very interested in who my father was. At Kristiansminde, however, there was a bailiff called Mikael Christian Thomsen who was alleged to be my father. For this reason I was given the surname Thomsen.

But there is much to suggest that it was really Lars Larsen who was my father. Every month my foster parents received a child allowance from Kristiansminde, and it was always double the stipulated amount - which the bailiff Thomsen certainly could not have afforded.

As a boy I often had the experience that people who visited my home would burst out: "Oh! Isn't the boy the image of Lars Larsen!" And there are other things too that suggest that Larsen was my father; I will come back to them later. He was unmarried, and I believe he was half-Jewish. He was born in 1838.

Sometimes my foster mother would be invited to Kristiansminde. I used to come too because my mother wanted to see me from time to time. My foster mother took me by the hand and then we walked the seven to eight kilometres to Kristiansminde.

Sometimes my foster mother would be invited to Kristiansminde. I used to come too because my mother wanted to see me from time to time. My foster mother took me by the hand and then we walked the seven to eight kilometres to Kristiansminde.  My mother was the housekeeper at Kristiansminde. She also managed the farm's dairy. I remember my mother as a mild and friendly woman who smiled lovingly at me. But I felt more secure when I held my foster mother's hand. I was too small to understand who my real mother was.

My mother was the housekeeper at Kristiansminde. She also managed the farm's dairy. I remember my mother as a mild and friendly woman who smiled lovingly at me. But I felt more secure when I held my foster mother's hand. I was too small to understand who my real mother was. My mother always called him "husband"(Translator's note: The Danish "husbond" (no longer in current use) is ambiguous meaning both "master" and "husband".). As a boy he had been adopted by a countess and from her inherited Kristiansminde, Kolskegård and Store Revstrup, which he later sold.

When he was staying at one of the other estates my foster mother would sometimes be invited to Kristiansminde. I used to come too because my mother wanted to see me from time to time. My foster mother took me by the hand and then we walked the seven to eight kilometres to Kristiansminde. Since I was used to only a small, spartan home it was a great experience for me. Here there were large elegant rooms with carpets on the floors and tapestries on the walls. The estate had many animals and its own dairy, which my mother managed with the help of certain girls. I remember my mother as a mild and friendly woman who smiled lovingly at me. But I felt more secure when I held my foster mother's hand. I was too small to understand who my real mother was.

After each visit my mother saw to it that a farmhand drove us home in a horse and cart.

Did your mother never visit you in Moskildvad?

Yes, she occasionally came to see us. And she promised me that I would certainly be allowed to study when I grew up. Then I could become a schoolteacher.

But she died when I was eleven years old. She got cancer and was taken from Kristiansminde to Hjørring County Hospital (Hjørring Amtsygehus), where she died on 9th November 1901. She was operated on for a cancerous tumour and was given a blood transfusion. At that time, however, the doctors did not know anything about blood types. In her last months she lived exclusively on milk and died a few days after the operation at the age of 53.

I went to the funeral at Kristiansminde. Her coffin lay open in a room there and I sat on a chair near the coffin while the door was open into the dining-room where a horde of guests sat eating a huge dinner. I thought it was an unappetising arrangement, but that is how things were done at that time.

I can remember that Lars Larsen walked backwards and forwards moaning, "Oh, my poor Christine, my poor Christine!" with tears running down his cheeks.

In the churchyard at the old Sindal Church I noticed that his eyes never left me for a moment.

He himself died ten years later at the age of 73.

Did you inherit anything front your mother?

She left almost nothing. Only a few volumes of Family Journal (Familie Journalen) and a wardrobe containing some clothes. My foster father sold the wardrobe for 35 crowns, which was then put into a bank-book towards my confirmation.

But I was happy to inherit so many Family Journals; I had always lacked reading matter. There was never any money to buy magazines or books.

How would you describe your childhood home Moskildvad?

I was happy, even though it was very small and spartan. I grew up with my two slightly older foster brothers. My foster parents were almost kinder to me than to their own two boys.

In the house there was only one living-room, and it was not very big. We lived, ate and slept there.

There were two beds filling the entire length of one side of the room. We three boys slept in one bed and our parents slept in the other. There was also a table and some chairs as well as a chest of drawers and a stove. That was all. At that time there was no central heating, radio, television, telephone, electric light or even a toilet.

Opening off the room there was a door to a small kitchen, from which one could go straight into the cowshed. The door opened directly onto where the cow stood. There was also space for a couple of pigs and some hens. And finally there was a barn.

When I was fourteen years old the house was rebuilt so that we also had a bedroom and a scullery. But there was still no toilet, not even a privy. One just went out to the cowshed and squatted in a corner.

What can you tell us about your earliest childhood memories?

The first thing I can remember was a little episode when I was a few years old. We were eating at the table in the living-room. We had rice pudding; my mother thought that I ought soon to be able to feed myself with a spoon. But when she put the spoon in my hand I could not guide it to my mouth by myself, and most of the rice pudding ended up in my eyes. So I was quickly finished with that!

The house had a straw roof, which on one side reached almost down to the ground. In the winter when there was snow the boys amused themselves by sledging down the roof from right up at the base of the chimney; but they were not supposed to.

My foster mother kept the house nicely clean and fed us well. At that time vegetarianism was an almost unknown idea; since at that time it was thought necessary, we ate a good deal of meat and fish. One could get good fresh fish from Frederikshavn. My consumption of meat and fish was, however, minimal, and if at any time an animal was to be slaughtered I ran a long way away. It was a nightmare to me.

The floor in the living-room was scoured white. Every week my foster mother went down on her knees and scoured the floor with a little sand and a handful of straw. Domestic appliances such as vacuum cleaners were totally unknown at that time.

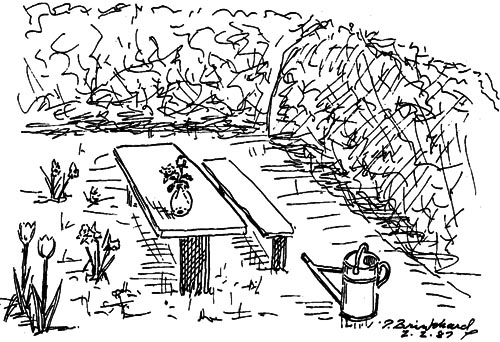

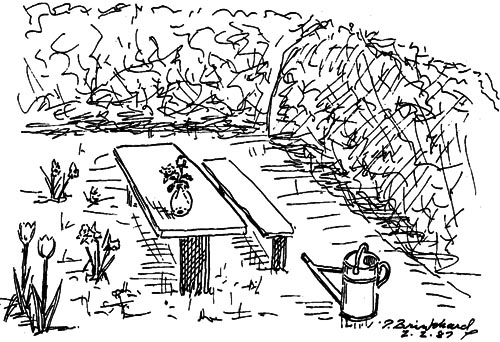

A small part of the five and a half acres attached to the house was laid out as a garden where there were both flowers and vegetables. My foster mother had arranged a corner of it as my own little private garden with a little table and a bench. On the table there was a vase. One day I discovered a 5-øre coin in the vase. When I ran into my foster mother and showed it to her, she said, "Our Lord has given it to you because you are a good boy!"

The land around the house was very hilly and I was very fond of sitting on the top of a hill, from where I could see far around. I could see the train that ran between Hjørring and Frederikshavn. I would sit on this hilltop and dream myself far away. I felt that something other than this little world must exist. One day someone gave me a pair of binoculars; this was the most perfect present - with them I could see all the way to Tolne Hills!

In the evening my two foster brothers and I were put to bed early so that our parents could have some peace. Our father sat and read the daily newspaper, the "Vendsyssel Times (Vendsyssel Tidende)", and our mother sat with her needlework. But sometimes it was difficult to get peace. We three boys lay in the same bed, with me in the middle. My foster brothers liked to lie and nudge me and tickle me so that I couldn't help laughing. Our father shushed us but in the end the cane was brought out and we were for it. But it was really only in fun. He hit only on top of the quilt, and I at any rate, who lay well protected, could not feel anything. The more he hit, the more I laughed. I was always very easily provoked to laughter.

Part of the house had a straw roof, which on one side reached almost down to the ground. In the winter when there was snow and our father was not at home my foster brothers amused themselves by sledging down the roof from right up at the base of the chimney.

Part of the house had a straw roof, which on one side reached almost down to the ground. In the winter when there was snow and our father was not at home my foster brothers amused themselves by sledging down the roof from right up at the base of the chimney.  My foster mother had arranged a corner of the garden as my own little private garden with a little table and a bench. On the table there was a vase. One day I discovered a 5-øre coin in the vase. When 1 ran into my foster mother and showed it to her, she said, "Our Lord has given it to you because you are a good boy!"

My foster mother had arranged a corner of the garden as my own little private garden with a little table and a bench. On the table there was a vase. One day I discovered a 5-øre coin in the vase. When 1 ran into my foster mother and showed it to her, she said, "Our Lord has given it to you because you are a good boy!" My foster brothers began to go to the "Station School (Stationsskolen)" in Sindal. One day the teacher came and asked my foster mother, "Where are your two boys?"

"They are at school!"

"No, they haven't been there all week!"

She was very surprised at this, but then she understood that they had been playing truant and gone to the woods instead of to school.

She stood there ready with the cane when they came home. And then they both got a thorough thrashing. I thought it was such a terrible sight that I ran far away into the field.

One Sunday, when I was about six, I had some new clothes with shiny buttons. With my foster father I went down to the meadow where there had been a peat bog. There was a ditch, and I amused myself by jumping to and fro, to and fro. Suddenly everything went black. I thought, "What is this?" I had fallen into the ditch, which was filled with cut slices of peat. Luckily my foster father was at my side and managed to pull me up.

When I came home to my foster mother she was very angry and I was very close to receiving my first thrashing. But if I had drowned she would have cried.

Were you not always trying to rescue flies and other creatures that were in difficulties?

Yes, that's true. Sometimes I would see a couple of flies or other small creatures stranded in a little water that was spilled on the table. I would try to help them.

"Kill them!" said my foster mother.

"Kill them? No, no - one can't do that; then I couldn't expect Our Lord to help me if I were drowning. I am a kind of Our Lord to them!"

"You are really crazy!" she said. She thought a little about it, but that kind of thing was not normal to her.

One of the great experiences of my childhood was the annual national meeting of the Home Mission (An evangelical branch of the Church of Denmark) that took place in the woods very near my home. It was in the summer and it was almost always lovely weather that day.

Many of the participants arrived in Sindal by train and then walked out to the woods. They came right past my home in their festive clothes, many of the women with fine parasols. It was such a long way to walk in warm weather that there was always someone who came in to ask for a glass of water.

Didn't they use the opportunity to proselytize?

Yes, some of them tried to preach to my foster mother. One of them asked, "How is your relationship to Our Lord?"

"Our Lord and I get along just fine!"

"Oh - because I spoke to Our Lord before I left home. Have you spoken to Our Lord today?"

Even though my foster mother was religious she didn't believe in that kind of thing, and when they had left she said, "Talk to Our Lord? What a load of rubbish!"

In the mornings my two foster brothers were given cups of coffee before they went to school. Eventually it was my turn to be given morning coffee, and, since the cups were still on the table, my foster mother poured my coffee into one of them. I made a bit of a fuss about this since I wanted a clean cup. She couldn't understand that; she had no feeling for that kind of thing. So I turned the cup round and drank from the opposite side.

"You and your fine manners! It must be because of the rich trash you come from," she said. But apart from that she was always kind to me. She only once lashed out at me, but even then she missed.

I had a pet name: it was "Titte". On my first day at school we had to tell the teacher our names. I said, "Titte Martinus Thomsen!"

"Titte," said the teacher. "Is your name Titte?"

Then the children laughed and said, "Now peep (Translator's note: Untranslatable play on words. The Danish "titte" means "peep" or "peek" as in "bo-peep" or "peek-a-boo".) at one another!"

I went to the station school for four years. There were two teachers, one male and one female. On the roof of the school there was a stork's nest that was used every summer by a pair of storks. It was Denmark's most northerly stork's nest.

After my four years at that school I was moved to a new one, built out in the country among some large farms. Here there was only one teacher and in the summer and autumn there was school only twice a week from 7 to 10am.

What did you actually learn in school?

Psalm verses and catechism. And a little geography and arithmetic. And sometimes a little Danish history and nature study.

One day the teacher explained that the Earth was round like a globe. When I came home from school I told my foster mother what the teacher had said, but she was very sceptical. "What a lot of nonsense - you can see for yourself that it is flat!"

When I was nine my two foster brothers had gone into service and I was now alone at home with my foster parents. But then they adopted a little girl who came from a very poor home.

It was very self-sacrificing of my foster mother: she had taken care of me and her own eleven children, yet she was now ready to take care of yet another child. The little girl was called Frida and I often went for walks with her in her pram.

I can tell you about a few incidents from when I was nine or ten years old. Up to that time I had actually never heard music. Then we had neither radio, gramophone nor television, and there were few that could afford a piano. I was walking past the parish police officer's house, which lay hidden behind a hawthorn hedge.

I had been on an errand for my foster mother and now I heard the most beautiful piano music pouring out of a window, played by the parish police officer's wife. I stood fascinated and listened until the music stopped. I felt a violent desire to learn to play myself.

Seven years later I got a job working for the parish police officer and then his daughter sometimes played for me. But I will return to that later.

One summer day I went for a walk with my foster mother. Having left the house and gone into the woods, we lay down on the grass to enjoy the sun. We fell asleep, but a little later we woke up because a fox was sniffing at us. There were foxes' lairs in the woods, but it was the first time I had seen such an animal.

Our nearest neighbour had a little girl called Petra. For a couple of years she was my only playmate. Although she was three years younger than I was, we played well together, and when she was seven years old and began to go to school I helped her with her homework and taught her the letters of the alphabet.

One day some fairground performers came with their tents to Sindal. One of the tents advertised "Living Pictures". I had no idea what it Was - but it turned out to be films, which at that time were quite new and unknown. A child's ticket cost 15 øre. I got the money from my foster father and set off on my way.

Inside the tent there were some long rows of benches, and the first four rows were for children.

When I was a child it was not usual to have one's photograph taken. But one day, when I was eleven, a photographer came to my school. My foster mother gave me 25 øre so that I could buy one of these group pictures. The above is an enlargement from this group picture, and it is the only photograph that exists of me as a boy. I can, however, remember that in my childhood home there was photograph of me at eight years old where I stood beside a dog that was also eight years old. But that photograph has disappeared. I have never managed to trace it.

When I was a child it was not usual to have one's photograph taken. But one day, when I was eleven, a photographer came to my school. My foster mother gave me 25 øre so that I could buy one of these group pictures. The above is an enlargement from this group picture, and it is the only photograph that exists of me as a boy. I can, however, remember that in my childhood home there was photograph of me at eight years old where I stood beside a dog that was also eight years old. But that photograph has disappeared. I have never managed to trace it.  One day some fairground performers came to Sindal. In one of their tents one could see "Living Pictures". At that time they were quite new and unknown.

One day some fairground performers came to Sindal. In one of their tents one could see "Living Pictures". At that time they were quite new and unknown. I sat with the other children and the show began.

Three short films were shown, each lasting only five minutes.

The first film showed some wild animals in a jungle. The next was from Paris, where one saw some of the very first cars driving around the city streets. The last film was from Spain and showed bull fighting in an arena.

I thought it was a pity for the bulls that they were to be killed, but I also thought that it was exciting and impressive that one could make such living pictures.

Another time I had to do an errand in Sindal in the late evening. The moon was shining brightly when I was to return home. Near the railway station there was a place where the train to Frederikshavn passed by a bridge over Uggerby Stream (Uggerby Å). From the road one could see this bridge; it lies quite close by. I stopped a little and looked down into the water that flowed slowly under the bridge.

Suddenly I saw something remarkable. Under the bridge there emerged the figure of a woman. Her hair hung in two plaits below her shoulders and she was wearing a checked dress. It was as if she came out of one granite wall and floated above the water. And, without leaving ripples in the water, she disappeared into the bridge's opposite granite wall.

I got goose-pimples and waited in astonishment to see if anything else happened. But nothing did, so I hurried home to tell my foster mother what I had seen, but because it was so late in the evening I did not tell her about it until the next morning.

She said merely, "Oh well - there have been many who have killed themselves there!"

For her, supernatural things were not unknown.

In the neighbourhood there was an old house whose inhabitants were for some years plagued by hauntings in that they could hear a child crying. The sound came from the floor in the living-room. When they broke up the floor one day, they found the skeleton of a little child. At one time someone had lived in the house and had got rid of a newly born baby by burying it under the floor.

It was common knowledge that there were women who could carry out witchcraft and black magic.

One of the most remarkable stories that I often heard was about a poor woman who had no money to buy milk, but was nevertheless able to get it in a certain way. When she saw that her neighbour's cows were out in the field with milk in their udders she fetched a couple of awls. The shaft of the awls had the form of a cow's udder. She stuck the awls up in the ceiling-beam of the low-ceilinged room. Then she began to "milk" the awls - and milk really came out of them. At the same time one of the neighbour's cows lost her milk and when the cow was due to be milked no one could understand where the milk had gone.

At that time it was common in old houses to have a "Cyprianus", a book of magic, which was not to be removed from the house. A genuine Cyprianus was from the Middle Ages and was written in red ink or blood. In my home we too had a Cyprianus. It was a little unbound book; I do not know if it was written in blood, but the letters were at any rate red. It was much older than the house, and it was so faded and worn that most of it was unreadable.

It was said that one day the previous owner of the house had wanted to get rid of the book. It was lying on a shelf in the living-room; he took it down and went to the kitchen range and threw it into the fire. When he came back to the living-room a little later the book was again lying in its old place on the shelf.

The book was full of old household remedies, invocations and mysteries. As I said, most of it was unreadable, but I remember there were instructions as to how a lad could win the love of a girl. He should take an apple to bed with him in the evening and let it lie in his armpit all night. The next day he should give the apple to the girl, and if she ate it she would be just as fond of him as he was of her.

Another piece of advice could be used by a farmer who wanted to irritate his neighbour, or who wanted to prevent horses and carts approaching his farm. By full moon he should dig a little furrow across the road. In this furrow he should bury the intestine of a pig, and then he should smooth the surface to hide the furrow. And now it would be impossible for horse-drawn vehicles to approach, for no horse would pass the buried intestine of a pig.

Did you have any duties at home?

Yes - I had to muck out the cow and the pigs - and the henhouse; from the stream that ran past the house I had to fetch water for the animals; and for the household I fetched clean spring water from a pipe.

I had also of course homework that had to be done.

Sometimes one of our sheep would give birth to a lamb, which would be very pampered. I often had to help the lamb to drink milk from a feeding-bottle. I could not understand how later anyone could have the heart to slaughter the lamb.

At the age of twelve I got a job as a herd boy on a big nearby farm called "Ulstedbo". It had large fields that were later parcelled out. Though I still lived at home and went to school, I looked after the cows in the field. Together with the hands I was given food at the farm. But it was such poor food that I did not eat much of it. I got much better food at home.

How many cows did you have to look after?

There were 30 to 40 cows, and it was a very large field. There was not even a fence at that time, which is why they had to be taken such care of. I drove them around and they ate a lot of grass; when they were satisfied they lay down.

Then I could rest too - and on rare occasions I had something to read. Otherwise I could pass the time by carving whistles, cows or stalls from twigs.

Towards evening I drove the cows home to the farm. In the cowshed they all knew which stall they should be in. I thought that it was a lovely job.

-----------------------------------

To be continued in Part Two

>> © Martinus Institut 1981, www.martinus.dk

You are welcome to make a link to the above article stating the copyright information and the source reference. You are also welcome to quote from it in accordance with the Copyright Act. The article may be reproduced only with the written permission of the Martinus Institute.